The Watta community: From lords of the forest to desperate struggle for survival

By Farhiya Hussein |

They understood the language of the wild animals, birds, and even the attitudes of trees well enough to predict weather changes and calamities.

The Watta community is an indigenous community in Kenya striving to adapt to contemporary civilisation and chaos.

They adapted to forest life, subsisting on hunting and gathering, as evidenced by their children, who still enjoy hunting during the holidays.

Keep reading

Mahmoud Dara, 87, reminisces about life years before independence and wishes he could reverse time and return to the old days, away from the noise of the industrial revolution.

“We used to lay traps to catch small wild animals in the forest. We lived a life full of harmony and we were a family unit. Unlike today, life was not much of a struggle,” he said.

According to Mahmoud, the Watta community were the lords of the forest at the time. They understood the language of the wild animals, the birds, and even the attitudes of trees well enough to predict weather changes and calamities.

“We were friends with animals and birds. If we needed water, a bird would emerge singing in the dry season and it would lead a person to a source of water in the forest,” he said. The same, he said, would also happen searching for food, especially honey.

The Watta elder said that since the community lived in the Boni Forest, they contributed to its sustainability.

He added that they protected wild animals, especially the Big Five, from poachers.

“The Big Five were our pride since we didn’t like noise, we hated guns and would respond fast to any gunshot and counter any activity related to it because we believed they were our property, our herd,” he said.

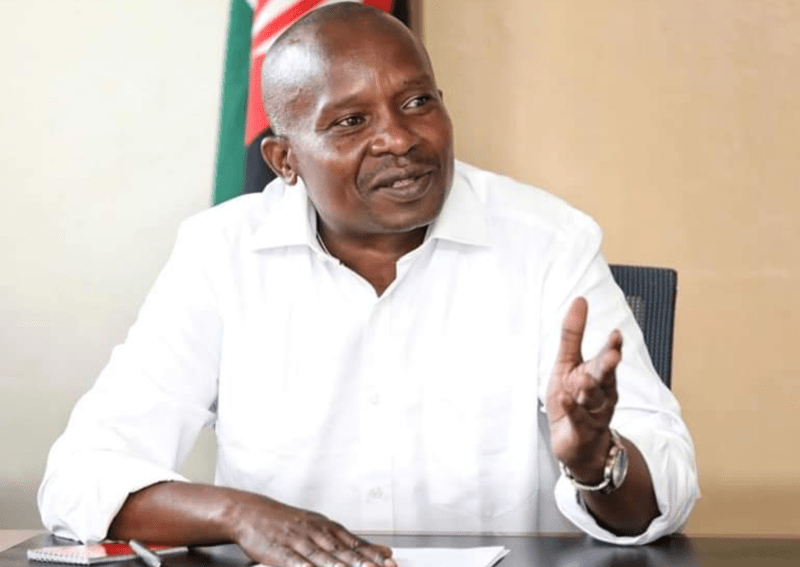

Mahmoud Dara, 87, reminisces about the old hunting and gathering lifestyle during an interview at Watta Hamesa Village in Tana River County. (Photo: Farhiya Hussein)

Mahmoud Dara, 87, reminisces about the old hunting and gathering lifestyle during an interview at Watta Hamesa Village in Tana River County. (Photo: Farhiya Hussein)

Their pride in the wild animals earned them the trust of the Kenya Wildlife Service.

They ate wild fruits, tubers, and vegetables prepared traditionally by elderly women.

Fatma Dabaso, 82, said that roots such as sweet potatoes, cassava, and yams were wild delights found in the forest surrounding River Tana.

“They were hard to come by, so if a place with plenty of them was located, we moved there until it was finished,” she said.

Food

Foods like rice, cooking oil, or salt were alien to them. Their cooking oil was derived from animal meat and nuts.

Most of their food was boiled, and they used spices derived from the bark of trees, leaves, and roots, to give the food the flavour they wanted.

“We didn’t have all these spices we see in shops today. Even our salt came from wild animals; I fancy that lifestyle,” she said.

Dabaso said the current eating habits are cosmetic and toxic as most things are chemically prepared and reduce life expectancy.

She teaches her grandchildren how to make food the traditional way, but laments that some of the leaves they used for spices have become scarce.

Fatma Dabaso, 82, a member of the Watta community, during an interview at Watta Hamesa Village in Tana River County. (Photo: Farhiya Hussein)

Fatma Dabaso, 82, a member of the Watta community, during an interview at Watta Hamesa Village in Tana River County. (Photo: Farhiya Hussein)

Deforestation and industrialisation have pushed them out of the forest, forcing them into a noisy life that they describe as difficult to survive.

“Today you must have money if you want to eat. You must work so hard to get money and buy food, or else you will die of hunger. Even meat today has become rare; it has become a privilege,” said Esha Dokota, a 71-year-old woman.

Dokota said modern life has caused them a lot of distress, making each day a survival of the strongest.

“The government pushed us out of the forest; they said they were conserving the forest. Even before we could move out, poaching began and trees were being felled for timber and carried away in big trucks,” she said.

She said removing them from their comfort zones has caused them to scatter all over the region as they look for new settlements.

“We welcomed the Pokomo here but, today, they are the ones apportioning us land to settle on while other communities don’t even want to associate with us,” Dokota said.

When it comes to job opportunities and leadership, the community feels greatly disadvantaged.

Fatma Kitole, an activist from the community, notes that most of their youth are not hired by the county government when opportunities arise.

“We are in a highly ethnicised leadership structure. Two major communities control the county assembly and one controls the executive. When opportunities arise, they slot their people no matter how learned our people applying for those slots are. The same happens with national government jobs,” she said.

She appealed to humanitarian organisations to focus more on supporting the community in education, among other enlightening engagements.

“If we can have 20 people from this community with quality education and exposure, then we shall be sure that we can take positions in areas of influence and create policies that will affect our lives positively,” she said.