Why is South Africa still waiting for a female president?

The country has yet to produce a female president—something the upcoming general elections are unlikely to change.

South Africa has one of the world's highest rates of female parliamentary representation in the world and boasts one of the most progressive constitutions.

Yet the country has yet to produce a female president—something the upcoming general elections are unlikely to change.

Related Stories

Of the more than 50 parties in the running on May 29, only a handful are led by women. The five largest are all headed by men.

"It is rare for a woman-owned party to stand, succeed and be sustainable," said Colleen Makhubele, one of the few female party chiefs, who runs the small South African Rainbow Alliance (SARA).

The dearth is despite South Africa ranking 11th globally for female representation in parliament, just below Sweden and higher than Finland.

Women played a major role in the anti-apartheid struggle and have held important government posts since the advent of democracy in 1994.

About half the country's ministries, including the key departments of foreign affairs and defence, are currently run by women.

Women's rights activists say the reason partially lies in the disconnect between the liberal views on which democratic South Africa was founded, and what remains a fairly conservative society.

The rainbow nation's constitution lists "non-racialism and non-sexism" as the country's second founding value after democracy itself. Yet many still see women as fit to lead their families—but not the nation.

About one in five respondents to a 2017 Ipsos survey said that a woman's place was in the home. Moreover, 22 per cent thought men made better political leaders.

This results in women often being overlooked when parties choose a leading candidate, said Bafana Khumalo, co-director of the NGO Sonke Gender Justice.

"Women are seen as important, but not to be voted into power," he said.

Makhubele of SARA, a former Johannesburg council speaker, said she has to work twice as hard as her male colleagues to win votes, funding and media coverage.

Missed opportunity?

Attitudes are slowly changing.

A 2020 poll by Women Deliver, a non-profit, found 91 per cent of respondents believed gender equality was important.

Forty-three per cent supported the government taking action to achieve equal representation in politics, and 69 per cent backed gender quotas.

The latter are already implemented by the ruling African National Congress (ANC) and the leftist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), the country's third-largest party.

The second-largest party, the liberal Democratic Alliance (DA), had a female leader between 2007 and 2015.

But that's not enough, said political analyst and author Susan Booysen.

"I'm blaming political parties for not systematically nurturing women's ascendancy in party politics to get them to the top. Women don't see that systemic mentoring and promotion," she said.

Parties might be missing out.

Women make up more than 55 per cent of registered voters in the upcoming elections and are seen as key drivers of support.

"They're the ones who make sure the people they live with go and vote on election day," said Zama Khanyase of the ANC's youth league.

The ANC is largely expected to get less than 50 per cent of the vote and for the first time, lose its absolute majority in parliament when South Africans head to the polls in a month.

That could force it into a coalition to remain in power.

After the parliamentary vote, national assembly lawmakers then appoint a president.

Top Topics This Week

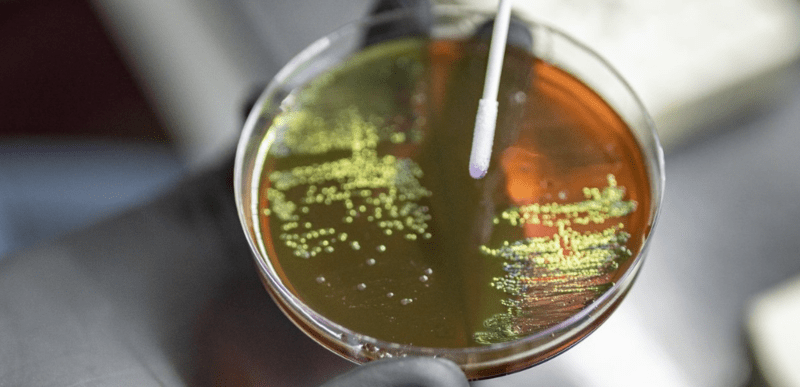

Floods in Kenya

waterborne diseases

floods crisis

Huduma Centre

kenyan ID

Police abstract

illegal mining kenya

Mining Cabinet Secretary Salim Mvurya

CS Ezekiel Machogu

Teachers Service Commission

Early Childhood and Development Education (ECDE)

Council of Governors Chairman for Education Mutahi Kahiga

suicide

Kwale County

teenage girls

teenage pregnancy

NTSA

kenya road accidents

Thika superhighway

Haiti

Trending

Garissa set to host Northern Frontier's first industrial park as state releases funding

Barack Oduor

|

3 days ago

Eastleigh businesses back hawker evictions on Yusuf Haji Avenue following violations

Abdirahman Khalif

|

1 day ago

Learners report back to school across the country after floods delay

Eastleigh Voice Team

|

4 days ago

Floods bring blessing for youth harvesting metals from Nairobi River for resale

Abdirahman Khalif

|

1 week ago

EGYPT-UN-PALESTINIAN-ISRAEL-CONFLICT-BORDER-AID

Dennis Tarus

|

6 months ago